Defining Queer Aging

In this section, the concepts of age and aging are “queered”. By this, we are referring to several conflicting yet overlapping understandings of the term “queer”. “Queer” can be used as an adjective, noun, or verb. For instance, “queer” is often used as a shorthand for categories of gender and sexual minorities (“the queer community”), including but not limited to Two-Spirit, lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans, queer/questioning, intersex, asexual, and other affirming identities (2SLGBTQIA+) communities. As is evident in the acronym, “queer” can also refer to an identity itself (“I identify as queer”).

“Queer” can describe ways of being in this world that are strange, odd, peculiar—different from the norm. Queer can also refer to actions of resistance or defiance; what you do (to queer), rather than who you are (a queer). For example, one might queer notions of age and aging by challenging reductive binaries (e.g., young/old); interrogating essentialist notions of chronological age, sexual orientation, and gender expression; centering the experiences of aging and older 2SLGBTQIA+ individuals; troubling dominant or familiar representations of old age as cisnormative and heteronormative; or offering alternate possibilities for growing old outside of limiting and narrow age expectations. “Queer aging” thus refers to multiple and conflicting understandings all at once.

When queer persons have space and opportunity to share their experiences of and perspectives on aging, and the conditions and contexts that influence their aging processes, trajectories that differ from those of cisgender, heteronormative nuclear family narratives become visible.

Changfoot et al., 2022, p. 6.

Queer Time and Queer Aging

Stories about queer aging are intimately connected to the concept of queer time, that is, conceptualizations of time that exist outside of normative or linear (i.e., straight) temporal arrangements (Halberstam, 2005). For many queer, trans, and/or Two-Spirit individuals, the path to later life can look quite different (Dugan & Fabre, 2018; Pearce, 2019), and can altogether be cut short as a consequence of interlocking oppressive structures, including homo-, trans-, and femme-phobia, misogynoir, racism, and colonialism. For example, for many gay men and trans women, especially those from BIPOC communities, their aging was interrupted and curtailed by the onset of the AIDS epidemic, individual and state violence, and transmisogyny (Halberstam, 2005; Ramirez-Valles, 2016). Under previous and ongoing systems of oppression, stories of queer aging that document complicated feelings of resilience and vulnerability, grief and joy, loss and wholeness are thus inherently political and radical acts.

Queering Cultural Meanings of Aging

Relatedly, stories that “queer” age and aging denaturalize cultural meanings of age and aging and can expose binary age norms and discourses that shape what is and is not possible for aging individuals, including 2SLGBTQIA+ older adults. Popular representations of aging individuals generally either construct older age as a time of natural decline that narrowly entails loss (of health, sexuality, beauty, vitality, and independence), or as a successful extension of youth whereby one actively avoids or overcomes this supposed predisposition to loss (Sandberg, 2013). Both ways of representing aging and older people leave little space to value or celebrate the material specificities of aging bodies. To queer aging is to reject this simplistic dualism (among other reductive binaries), while acknowledging and re-evaluating material difference across the life course.

Stories of Queer Aging/Aging Queerly

Queer/ing aging is evident in the stories of Mary Gordon (Heart, Broken), Gisèle Lalonde (HAG Hair), and Carla Rice (Through Thick and Thin). These stories expose and critique normative expectations for aging and older women, including sexist, ageist, sizeist, and heterosexist assumptions, while imagining and celebrating resistant, proud, “disgraceful,” and capacious or wider (i.e., fatter) ways to age.

Video: Heart, Broken by Mary Gordon

Excerpt from Changfoot, et al., 2022, p. 6

“In Heart, Broken, Mary Gordon (settler, born in Mushkegowuk Cree territory, Northern Ontario, of Irish, Scots, and British immigrant stock) opens with the reflection, ‘I think, I think I’m aging into beauty,’ as she caresses ‘Winnie’, a papier-mâché sculpture that exudes pride in deep wrinkles, a toothy grin with spaces in-between and perky-nippled naked sagging breasts, whilst proudly describing herself as the ‘short, fat, queer, old doll I am.’ The light-heartedness of her opening, and affirmation of her queer prideful aging self, gives way to a sober mood as she shares the grief of the devastating loss of her grandson, foreshadowed by their ‘up and down’ road trip east, the opposite of the ‘Go West, young man’ progress narrative that dominates Western film. In an unflinching tone, she recounts that she was told by grief counsellors to say ‘he completed suicide’. Gordon next brings her viewer into her broken heart, introducing us to the Japanese medical diagnosis, takotsubo, also known as broken-heart syndrome, which is thought to be experienced mainly by women.

As she describes the syndrome, she focuses on the left ventricle of a heart, the defining feature of takotsubo (being similar in shape to an octopus trap, or takotsubo), which becomes enlarged in response to sudden overwhelming stress. The tone of the video shifts once again as Gordon turns to describe kintsugi, the Japanese art of mending broken pots, with its aestheticization of the beauty of broken objects mended back together. In Gordon’s storytelling, kintsugi becomes a metaphor for ‘unique cracks that leave different marks on each of us’, which signify ‘the essence of resilience’. The cracks appear suddenly but the mending is a slower, more enduring process.

In contrast to the linear heteronormative pathway associated with ‘successful aging’, Gordon brings our attention to the marks and breaks within and on each of us, the broken parts of ourselves that might show and that might not show, particularly the marks of unimaginable loss. Gordon shares what mended her broken heart: love and care for her grandchildren and family relations. Her queer pride in her joyous closing, ‘I am beautiful’, embodies the fullness and wholeness the story of her queer life and memory of her grandson offers, which importantly includes her loss and broken heart. Yet, from this loss, the mending and creation of queer life creates aging into beauty on Gordon’s terms. Holding the papier-mâché ‘Winnie’ (named after Gordon’s late mother) with joy in her video, she channels her mother and her grandson; they are always close with her. Deeply felt grief and loss, the continued presence of loved ones beyond their physical form, the temporality of mending which has no definitive end, and queer and aging pride are the many facets of aging, queered for how they expand understanding of aging to be capacious”.

Video: HAG Hair by Gisele Lalonde

Excerpt from Changfoot et al., 2022, p. 6.

“In HAG Hair, Gisele Lalonde (settler, queer, French Canadian) brings together two experiences of aging, her late mother’s aging, and her own aging symbolized by what she pridefully reclaims as her ‘hag hair’. Punctuated by the repetitive ding of an elevator arrival, her story opens with the joy of having ‘groovy, short, dark, hair’, which her friends and partner openly appreciated and loved. After her mom moved into her new apartment, Lalonde recounts how her mom would meet her at the elevator ‘all dressed up and ready to go’ to descend enthusiastically into a dollar store or a pub.

To mark a shift in time, Lalonde shows the camera a full view of her now luscious, long grey hair which also visually signals a shift with her mother who began to meet Lalonde at the elevator in her pyjamas. They would stay in, sharing homemade soup, a drink, and favourite TV program. Her mom would easily share one of her many memorable stories. Lalonde clearly loves her late mother and her own ‘hag hair’. ‘Hag hair’ expresses her emotions and transformation into a new form of her beauty, yet she also shares the sadness of her mother’s changing self. Continuing to relate with her late mother, Lalonde shares that claiming the hag has been freeing. She is a superhero with her cape of beautiful grey hair.

Lalonde’s experience of aging occurs in parallel with her late mother’s, showing that there are multiple and intertwined timescapes of aging for persons in relationship. In her story, Lalonde marks her own aging from dark short hair to longer grey hair alongside the aging of her late mother who would at one time be dressed ‘to the nines’ and ready for fun, but eventually became comfortable to stay in and cosset in pyjamas. As Lalonde embraces her ‘hag hair’, her mother declines in health. By sharing these stories of herself and her mother, Lalonde shows that there is no singular experience or trajectory of aging because aging occurs in interrelationship with people. This interrelationship reveals a cyclical dynamic, one that includes grief as decline occurs, and also joy as Lalonde celebrates her lustrous long grey hair, assigning it superpower capacities as it protects her from the ageism she experiences”.

Video: Through Thick and Thin by Carla Rice

- OC Open Captions

- Audio described

- Uncaptioned

Select a format:

Except from Rinaldi et al. (2016):

“In Through Thick and Thin, Rice explores embodied subjectivity as process, reflecting on her body history, entangled desire and desirability, and her aging body. She viscerally illustrates how discourse becomes lodged in the flesh. Desire/disgust, beauty/ugliness, hate/love, and fear/assurance interweave through the story of her body’s metamorphosis, refusing finality and closure. Rice describes a vintage plastic folding fan she was given by a woman with whom she shared an intimate and complex relationship, and explains that her ‘fan woman’ taught her how to embody a queer femininity at once subversive of heterosexist norms and submissive to cultural scripts about fat female bodies.

Rice’s narrative reveals the interplay of desire and disavowal as her body and her feelings about it have metamorphosed through the past and present in relation to the irreconcilable messages of affirmation and negation she has encountered. The dis/empowering strategies she learned converge with the hateful voices of childhood tormentors, which replay as she retches and purges for the last time. When Rice tells her fan woman about her wanting as well as her hunger, anger, and pain, she provokes a shift in and between them, beginning another phase in their ‘mutual metamorphosis’ (Shildrick, 2015, p. 23). Rice then opens a space in which the twinned notions of aging as decline or successful defiance (Sandberg, 2013) are shifted through their co-presence, returning to her fan as a queer symbol for her own aging.

The story’s imagery comprises a series of black and white photographs of Rice’s body in the present, as a woman in her early fifties. The images focus on the textures of her skin over her bones, muscles and fat: smooth and ornamented, relaxed and folding, wrinkled and puckered. The juxtaposition of these images with Rice’s story of entangled change can be understood in accordance with Margrit Shildrick’s Deleuzian understanding that ‘a human body is not a discrete entity ending at the skin… immersion in the indeterminacy and provisionality of multiple inter- and intra-connections is not simply the condition of living but the source of flourishing’ (2015, p. 24).”

Reflection Questions:

- What thoughts/feelings arise when viewing Rice’s film?

- What does the fan symbolize for Rice?

- What role do age and time play in Rice’s relationship to her complex embodiment?

- How does Rice’s story queer (i.e., make strange), or challenge us to think differently about, dominant representations of femininity, eating disorders (or disordered eating), aging, and queer women?

- When is the time of bodily change? Is there a singular time?

- Which types of bodily changes are viewed as acceptable, normal, and/or natural throughout the life course? Which ones are devalued or undervalued?

- Are some types of bodily change celebrated more than others? Where do you see this happening?

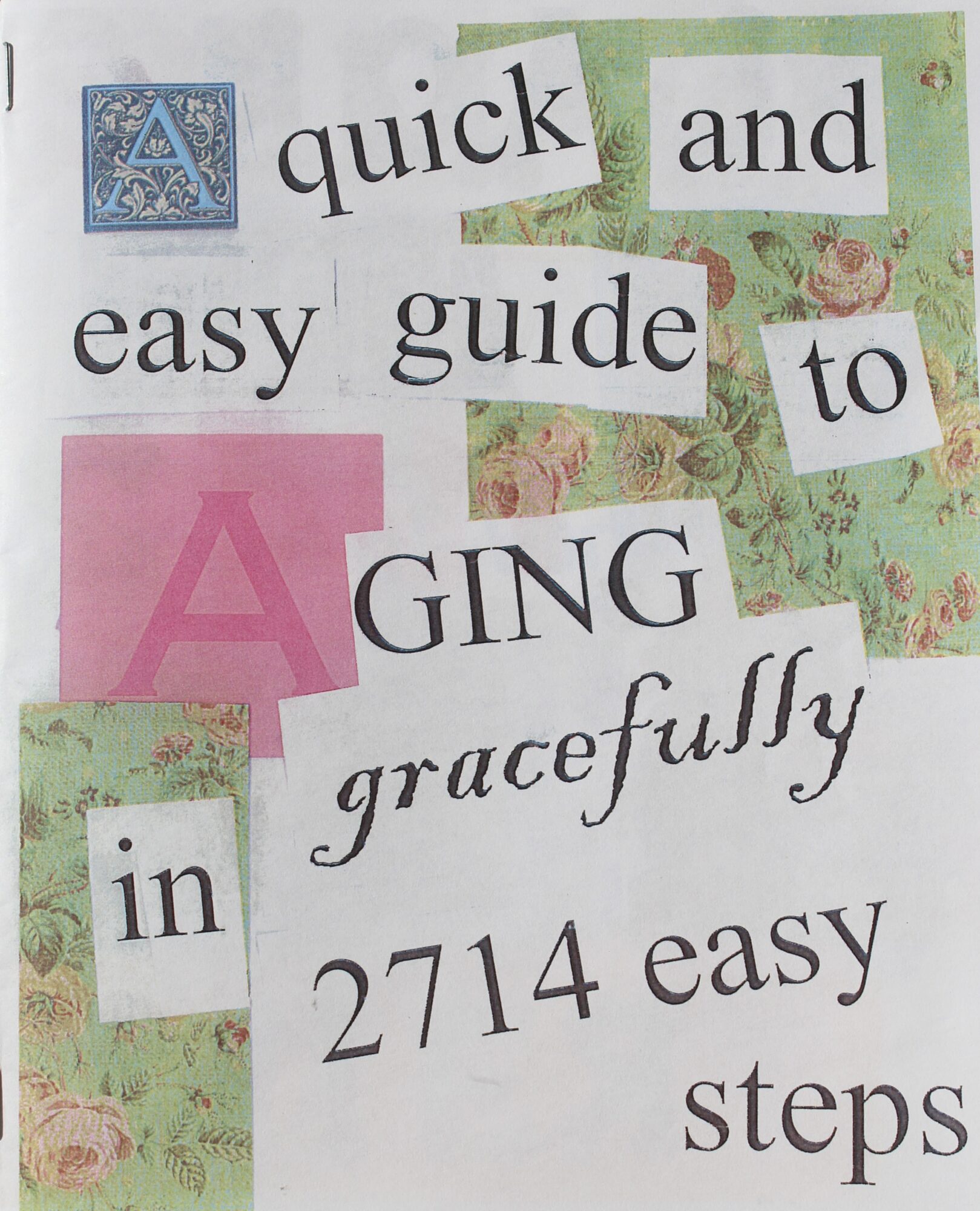

Activity: Craftivism

Political in nature, queer aging stories can be understood as speaking back to cultural and sub-cultural narratives, representations, and discourses that instruct aging women and femmes on how to look, behave, and act, while reclaiming disparaged and devalued signs of aging (e.g., silver hair, wrinkles, folds of flesh). Like storytelling, crafting holds the potential to explore and queer (or trouble) narrow and limiting depictions of and expectations for aging femininity.

Short for magazine, a “zine” is a form of craftivism (activism that uses craft to express a politicized message). Zines make use of both original and repurposed text, images, and mixed media to give voice to marginalized communities. They cover various topics and can be made by a group or an individual. Often political, zines allow those who are mis- or under-represented the opportunity to challenge dominant discourses in both critical and humorous ways. And since zines are often cheaply made and/or distributed for free, they have the potential to connect and empower devalued groups of people who might otherwise struggle to find community.

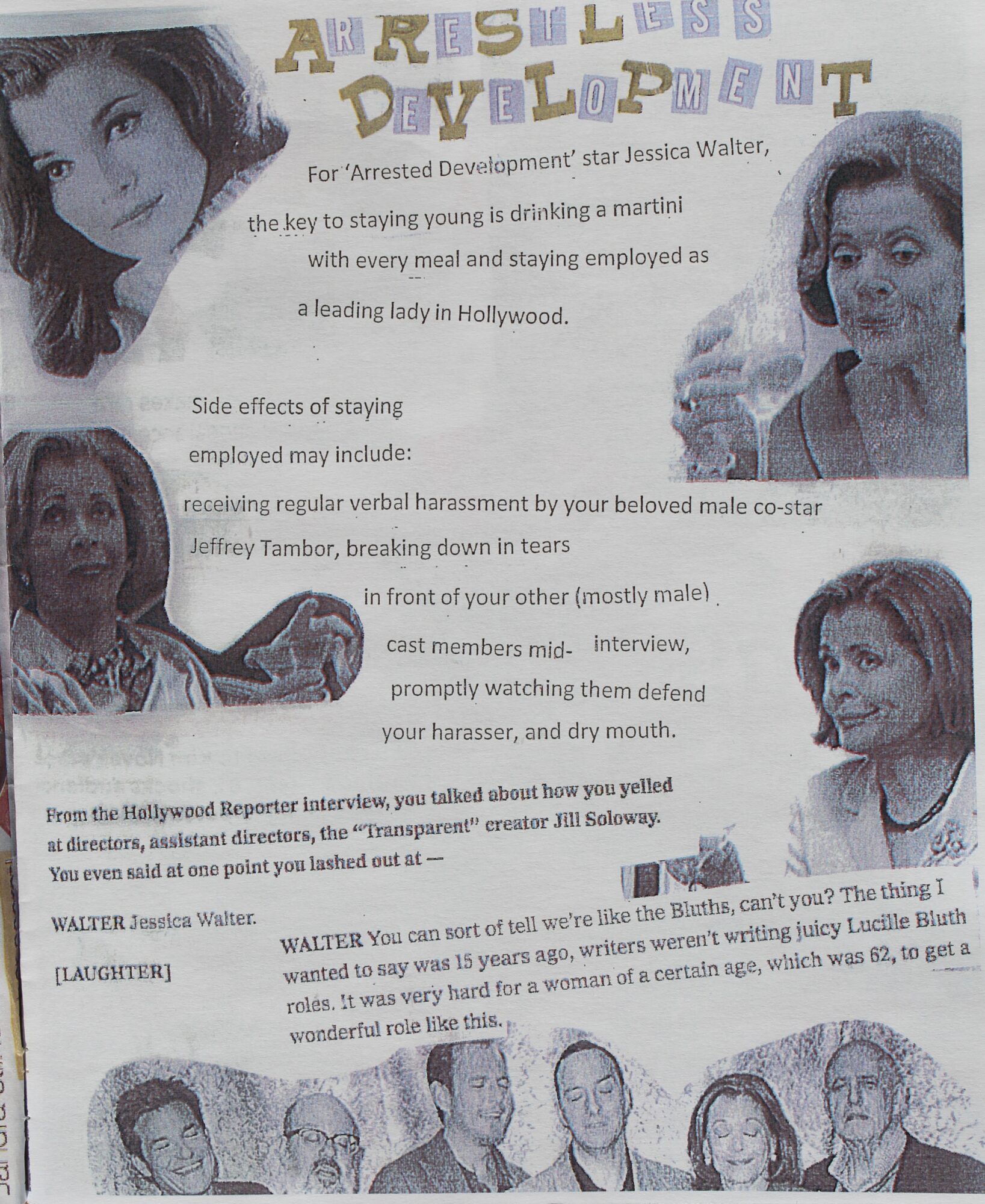

Gossip magazines are rich sites to examine contemporary discourses of aging femininity, including “graceful aging” discourses (Railton & Watson, 2012; Williams, 2015). In the cultural imagination, graceful agers are women who successfully balance effort and restraint, which is to say, “women should diet, but do so ‘sensibly’; exercise, but ‘in moderation’; dye greying hair, but to a ‘natural’ shade; wear make-up, but not appear ‘gaudy’; look ‘sexy’, but not act sexually” (Railton & Watson, 2012, p. 200). Importantly, the performance of graceful aging, including all the expected yet ridiculed body and beauty work to achieve this effect, should appear effortless and natural. A derivative of successful aging discourses, which implicitly champion young and able bodyminds, graceful aging is thus a complicated normative discourse that can reproduce ageist, ableist, and misogynistic attitudes.

Using gossip magazines, craft, and creativity, reflect critically on the topic of graceful aging in celebrity and popular culture.

In a small group, collectively identify, examine, and challenge graceful aging discourses by creating a zine about celebrity aging.

- Pick an aging celebrity (e.g., Liza Minelli, Jane Fonda, Judi Dench) and seek out two to three representations of your celebrity.

- Reflect critically on how your celebrity’s aging and gender is represented. You might ask some of the following questions of your representations:

- Is the featured celebrity being profiled because they perform aging femininity/masculinity properly?

- Is their aging treated as a problem or a pathology? If so, what are the details?

- Is the experience of aging, including bodily changes, celebrated or denied?

- What language or symbols are used to convey this?

- Is there a noted discrepancy between the celebrity’s chronological age and their appearance? How is this signified?

- Flip, challenge, or speak back to these discourses using humour, images, and text found in gossip magazines. Use your own words.

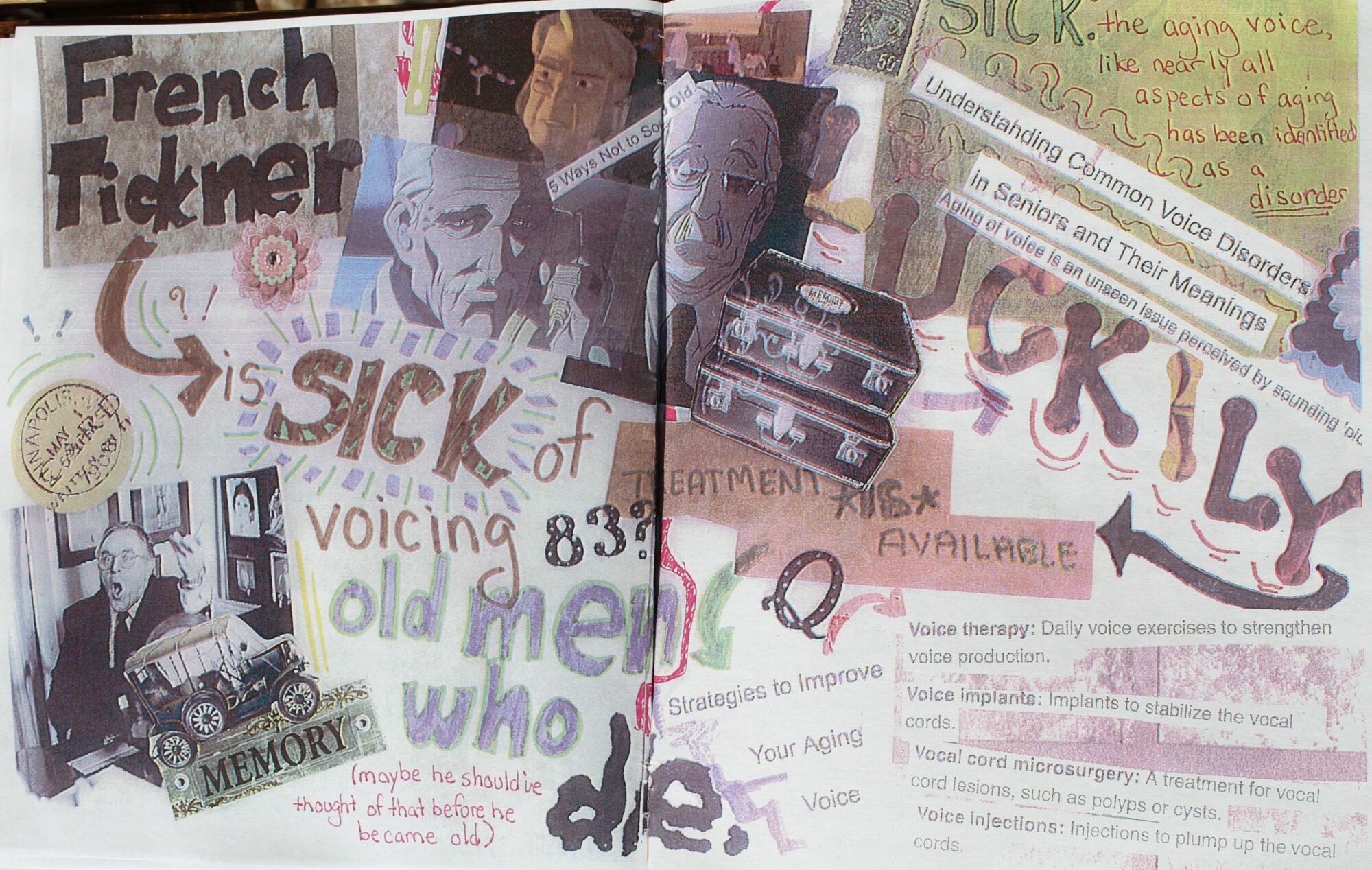

Here’s an example of a zine that was created by undergraduate students in Jami McFarland’s 2018 fourth-year course, “From Golden Girls to Raging Grannies: Feminist Perspectives on Aging”:

A version of an illustration by Naheen Ahmed featuring a silhouette of hands drawing against a peach-orange background.