Many crip cultural practices seek to create access for disabled people. In fact, many access practices might also be considered crip cultural practices. However, when access is part of a crip cultural practice it is not just a straight-forward logistical concern but is also engaged for its social, cultural and/or political meaning.

To understand the difference, let’s consider a few different ways of framing access:

Access as Inclusion

“Access as inclusion” describes a commonly encountered approach to access that positions access as a “doing,” as an action, and as something to achieve. This approach draws on a range of access measures that seek to include disabled people by addressing barriers that would prevent people from accessing spaces, services, or experiences. This approach understands access within a framework of compliance (e.g., through accessibility legislation) and often includes a list of pragmatic ways to improve access for disabled people (e.g., accessibility standards).

“Access as inclusion” aims to support disabled people by modifying spaces or systems. When there is a “misfit” between disabled people and the culture they are being included into, this approach typically requires disabled people to change themselves in order to fit in. When it is not possible for disabled people to conform to the demands and regulations of normative systems, they remain excluded. In both cases, the normative system remains intact and does not change. There is therefore a need to think beyond this framework to consider how access can be a means to cultural transformation and deeper structural change.

There are many other ways that we can approach, practice, and think about access in relation to disability and crip cultural practices. It is important to recognize how we conceptualize access because how we frame our understanding of access (i.e., who is designing access, who is centered in access plans, and the objective of access, be it for inclusion or transformation) informs how we practise access. How we frame access also informs the impact we have on spaces, as well as the experiences disabled people can have in these spaces.

Below we describe “critical access” (Hamraie, 2017), “open access” (Papalia, 2018) and “acces(sen)sibility” (Jimmy, 2020). These are three different frameworks for approaching access engage with and/or advance crip cultural practices. They also open the possibility of developing “access intimacy” (Mingus, 2011) a concept we define in the next section.

Explore Further

- READ: Hamraie, A. (2017). Introduction. In Building Access: Universal Design and the Politics of Disability (pp. 1–18). University of Minnesota Press.

- WATCH: Sheyfali Saujani, Reading Blind (2012), from Mobilizing New Meanings of Disability and Difference

- WATCH: Raya Shields, Untitled (2016), from Re•storying Autism in Education

- READ: Rice, C., & Mündel, I. (2019). Multimedia storytelling methodology: Notes on access and inclusion in neoliberal times. Canadian Journal of Disability Studies, 8(1), 118–148.

Access Intimacy

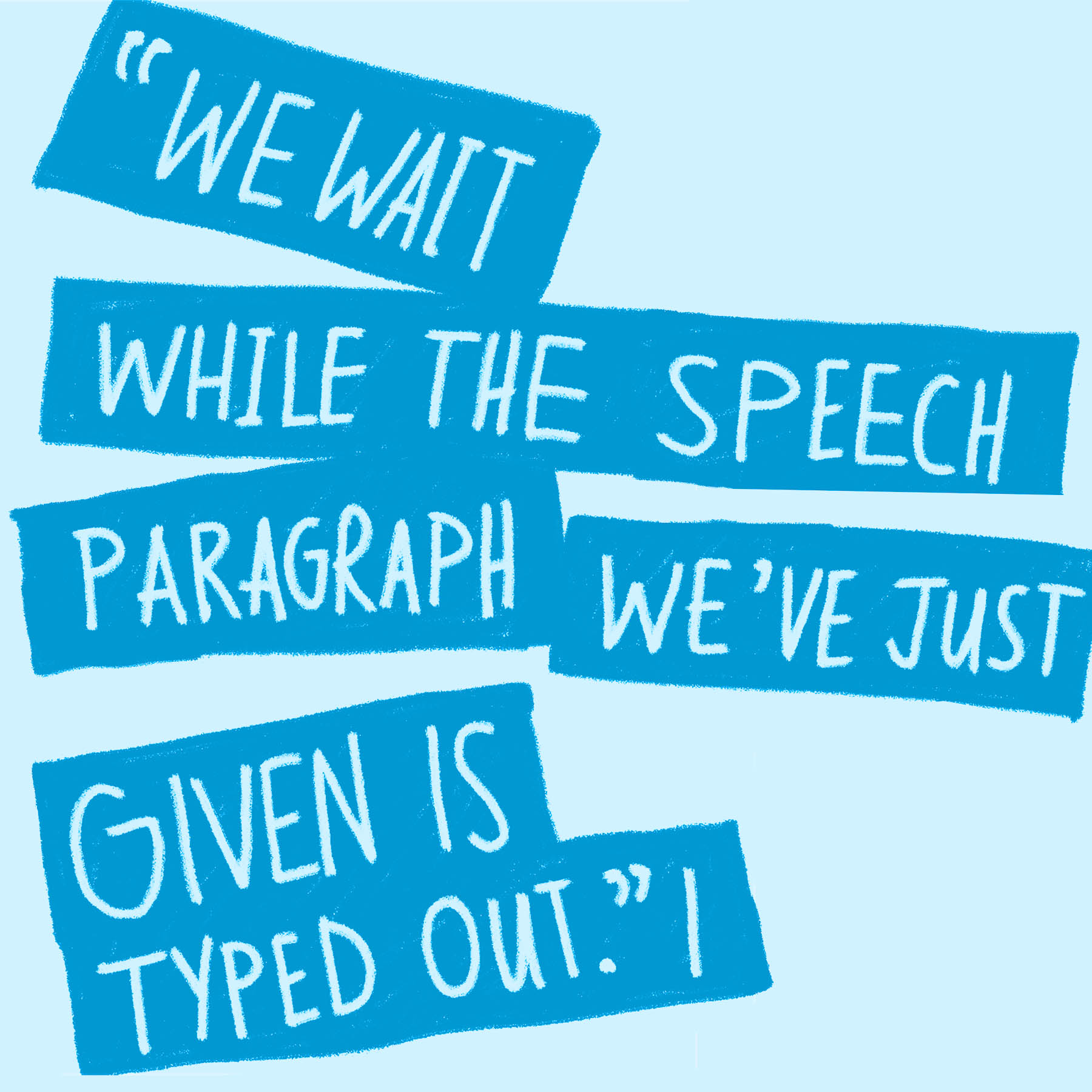

“Access intimacy” is a term coined by Mia Mingus to describe “that elusive, hard to describe feeling when someone else ‘gets’ your access needs” (2011, para. 4). It is not access that is provided out of obligation, rather, as Mingus notes, “Access intimacy is not just the action of access or “helping” someone . . . Sometimes access intimacy doesn’t even mean that everything is 100% accessible” (2011, para. 8-9). Access intimacy occurs when we approach access as a relational practice, as something that can be shared between people and attuned to together, in relationship and in community. When access is framed through the lens of compliance or obligation, or when it is positioned as a checklist of tasks to complete, it does not open the possibility for access intimacy.

We cannot always predict when access intimacy will emerge. Mingus observes that it can be built over time and it can emerge suddenly with someone you have just met. However, by engaging access as a critical and political practice, we set the conditions that can allow access intimacy to flourish.

Resource

Cripping the Arts Access Guide

The access guide that was created for Cripping the Arts Symposium shared all of the access features of the event and provided participants with ways that could support others in making the event more accessible. The guide opened the possibility for participants to experience a sense of access intimacy at the event.

Explore Further

- READ: Chandler, E., Ignagni, E., & Collins, K. (2021). Communicating access, accessing communication (Dispatch). Studies in Social Justice, 15(2), 230–238.

Critical Access

In Building Access: Universal Design and the Politics of Disability (2017), Aimi Hamraie develops the concept of “critical access.” This concept provides a framework through which we can be critical of access practices that hold inclusion as their end goal.

Hamraie offers a historical redress to current notions of access that position it as a “self-evident good” that is good for “everyone.” Instead, Hamraie recalls the early days of the disability rights movement and struggles for accessibility during the Independent Living Movement (ILM) of the 1960s, and foregrounds how this movement specifically centred disability experiences and politics.

While the Independent Living Movement led to significant legislative changes (e.g., the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) and the Accessibility for Ontarians with Disabilities Act (AODA)), Hamraie observes how since that time the notion of access has become depoliticized and distanced from its roots in disability experience and culture. We can find an example of this in the rhetoric of Universal Design and how it positions accessible design as something that is beneficial for everyone.

Hamraie asserts that we must reinvigorate access as a political project and work towards building access practices and plans that centre disability experiences. This means that the way we approach and practice access would be taken up through an anti-assimilationist politic that was aligned to disability culture, and which would aim to disrupt and rebuild (rather than to confirm, conform, and enforce) normative culture.

Undeliverable at Tangled Art + Disability

Undeliverable is a group art show curated by Carmen Papalia that was exhibited at Tangled Art + Disability in Toronto and the Robert McLaughlin Gallery in Oshawa in 2021-2022. This exhibition, which brought together six disabled, Mad, and Deaf artists: Vanessa Dion Fletcher, Chandra Melting Tallow, Jessica Karuhanga, jes sachse, Aislinn Thomas, and Carmen Papalia with Heather Kai-Smith. The artists investigated curation as a form of care by reimagining the demands placed on disabled bodyminds by arts institutions like museums and art galleries.

Many of the artists engaged with access in both practical and conceptual ways, as did the structure of the exhibition itself. For example, typically galleries include artist statements for each artwork, which offer spectators information about the piece. Since the artists in this exhibition were dealing with the added pressure of creating and installing work during the pandemic, some of those written statements were not ready when the exhibit opened. Rather than push the artists to complete these statements, the gallery opted to display the word “undeliverable” on the wall, adding the statements to the exhibition as they became available (Johnson, 2022, p. 30).

This approach drew attention to some of the barriers that disabled artists experience in the art world, and it upset the usual way in which an exhibition would be organized. This exhibition is one of many examples of how disabled artists are cripping gallery and museological practices.

Explore Further

- READ: Cachia, A. (2013). ‘Disabling’ the museum: Curator as infrastructural activist. Journal of Visual Art Practice 12(3), 257–289. https://doi.org/10.15353/cjds.v2i4.110

- READ: Sweeney, E. (2010). Shifting definitions of access: Disability and emancipatory curatorship in Canada. Muse Magazine: Canadian Museums Association 28(6), 23–25.

- READ: Rieger, J., & Strickfaden, M. (2018). Dis/ordered assemblages of disability in museums. In B. Hadley & D. McDonald (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of disability arts, culture, and media (pp. 48–61). Routledge.

Open Access

Carmen Papalia is a disability-identified artist and curator, who self-identifies as a non-visual learner, working out of Vancouver. In a 2018 issue of Canadian Art, Papalia put forth his framework of Open Access. Open Access resists the “checklist” approach to access that more traditional approaches to access tend to take up. Instead, it argues that access is a process of mutual exchange that is co-created by those present, each of whom bring their own body of knowledge and are ‘experts’ in their own right. Rather than aligning access with policies and enforcement, Open Access seeks to garner trust and intimacy between people by positioning access as “a responsive support network that adapts as needs and available resources change” (Papalia, 2018, para. 7).

Activity #2

Let’s think about how Carmen Papalia’s performance Mobility Device provides a good example of Open Access in Practice.

For this activity, first read through Papalia’s writing on Open Access (linked above). Then watch the performance Mobility Device [YouTube 09:11] and reflect on the following questions as you watch. If you’re doing this in a group or with a partner you can share your answers and compare your reactions.

Questions to reflect on while you watch:

- How is access approached in this video and who is responsible for it?

- What is different about the way access is portrayed in this video compared to how it might typically be portrayed?

- What principles of Open Access can you identify in Mobility Device?

- Would you describe this as an example of a crip cultural practice? Why or why not?

Acces(sen)sibility

Cree curator and artist Elwood Jimmy in ArtsEverywhere observes that when we take up access, “we very seldom question what this accessibility gives access to” (2020, para. 1). For example, he notes that access, when not taken up critically or as a political practice, can potentially lead to forms of inclusion that reinforce colonial structures, habits, and ways of being. Jimmy calls on us to instead approach access with a desire to “interrupt the satisfaction we have with the securities and the rewards we receive in the dominant system, so that we can clear the way to engage with and relate through what is unknown and unknowable, without trying to codify, translate, instrumentalize and appropriate it” (2020, para. 5). To embrace the disruptive potentiality of access requires that we not just do things differently but that we “be differently” (2020, para. 5, original emphasis).

Jimmy offers that we turn “accessibility” into “acces(sen)sibility,” a practice rooted in an Indigenous understanding of the senses. Acces(sen)sibility offers a “sense of responsibility and attention towards the different temporalities, rhythms, medicines, and bodies of different beings” in a way that tackles the ontological issues of separateness that are foundational to colonial violence (2020, para. 5).

Acces(sen)sibility provides a way of thinking about how we can frame access as a means of disrupting colonial systems so as to enact structural change.

Explore Further

- READ: Elwood Jimmy on Acces(sen)sibility

- WATCH: Temporality and Acces(sen)sibility – Eliza Chandler & Elwood Jimmy

Activity #3

In this cumulative activity you will revisit the list of barriers and access measures you compiled for your arts event in Activity #1.

Pick one of the access frameworks introduced in this submodule: critical access, open access, or acces(sen)sibility.

Review your answers to Activity #1, and reflect on and consider how you might change or adapt your answers if you were approaching the event through the lens of the access framework you selected.

Some questions you might want to ask yourself as you complete this activity are:

- In Activity #1, how was I framing or understanding “access” in relation to my imagined event?

- How did the way I was framing or understanding access (in Activity #1) impact or influence the kinds of access practices that I planned for the event?

- Do the access practices that I initially listed align with an anti-assimilationist disability politics? Why or why not?

- Are any of the access practices that I listed an example of a crip cultural practices? Why or why not?

- How might I reimagine different elements of this event so that they were rooted in crip cultural practices?

Tip

If you get stuck, consider how artists have reimagined access to align with crip cultural practices in some of the examples that follow…

A detail from a larger illustration by Josephine Guan, featuring hands signing the word “access” in ASL. This version is shown in shades of blue.