Many people have a negative perception of disability, understanding it as tragedy, loss, or simply as less-than in comparison to living without a disability.

The negative way that many people perceive disability is rooted in the historical and continuing oppression of disabled people, as well as the construction of non-disabled—or abled people as the norm—or “normate.” In reality, every person is different and there is no one best way for people to be.

Definition

Abled

The term “abled” describes someone who is not disabled. It is more inclusive than the commonly-used term “able-bodied,” which may not account for mental or neurological differences.

The Normate

Disability theorist Rosemary Garland Thomson explains how the norm or ideal notion of what a person should be is defined through its opposition to those who are labeled as “deviant” or not normal. She calls this almost mythical ideal “the normate,” and she describes it as follows:

… the figure outlined by the array of deviant others whose marked bodies shore up the normate’s boundaries. The term normate usefully designates the social figure with which people can represent themselves as definitive human beings. Normate, then, is the constructed identity of those who, by way of the bodily configurations and cultural capital they assume, can step into a position of authority and wield the power it grants them. If one attempts to define the normate position by peeling away all the marked traits within the social order at this historical moment, what emerges is a very narrowly defined profile that describes only a minority of actual people (Garland Thomson, 2017, p. 8).

To illustrate the concept of the normate, we can consider the work of David Bobier of VibraFusionLab. Bobier’s “vibrotactile” art reveals that sound is a vibration that can be experienced through senses other than hearing. Through his work, Bobier challenges assumptions about listening and perception, upending normative expectations for engaging with music and sound.

Ableism

Talila Lewis, social justice engineer and abolitionist activist, has developed a working definition of ableism that addresses the intersecting political causes of ableism.

A system of assigning value to people’s bodies and minds based on societally constructed ideas of normalcy, productivity, desirability, intelligence, excellence, and fitness. These constructed ideas are deeply rooted in eugenics, anti-Blackness, misogyny, colonialism, imperialism, and capitalism. This systemic oppression that leads to people and society determining people’s value based on their culture, age, language, appearance, religion, birth or living place, “health/wellness”, and/or their ability to satisfactorily re/produce, “excel” and “behave.” You do not have to be disabled to experience ableism (Lewis, 2022).

Reflection Questions

Responding to Talila Lewis’ definition of ableism, consider the following questions:

- How might a non-disabled (or abled) person experience ableism?

- Are all non-disabled people equally likely to experience ableism?

- How does ableism intersect with other dimensions of oppression?

In Crip Conversations: A Conversation About Racism and Ableism with Imani Barbarin, disability activist Imani Barbarin describes ableism as “interpersonal, institutional and societal discrimination against disabled people—it’s systemic and from the top” (Texas Center for Disability Studies, 2022).

In the video, Barbarin illustrates how ableism and racism are closely intertwined, using her own experience as a Black woman with cerebral palsy as well as historical and contemporary examples from the United States and beyond.

Activity

Intersections of Racism and Ableism

In the Crip Conversations video, Barbarin explains, “Every single day, our lives are dictated by both race and disability, regardless of what our individual race is.”

As you watch the video, please find specific examples of the ways that differences in ability disprivilege or privilege intersect with differences in race-based disprivilege or privilege (and disprivilege or privilege in relation to other dimensions of social location such as gender, class, and sexuality) in the following areas:

- Health care

- Employment

- Education

Ableist ideologies are deeply ingrained in the structure of our society, shaping policies and practices as well as attitudes. Because of ableism, disability access needs are often ignored, which results in exclusion.

Ableism or Disablism?

Some disability theorists would use a different term, “disablism,” to describe the oppression of disabled people. They may also use “ableism” in another way, specifically to describe the ways that abled people are privileged and the normate is positioned as the ideal.

For example, disability theorist Dan Goodley uses the term “ableism” to illustrate how disability is excluded from a society that only values normality. He writes, “Disability is the quintessential Other of neoliberal-ableist society. Ableism edits out lack and emboldens (hyper) normality” (2014, p. 33).

In the 2017-2018 Bodies in Translation kNow Access Collage, Sean Lee, Gallery Manager, Tangled Art + Disability, highlighted a quote from disability theorist and activist Mia Mingus about how ableism is interconnected with and inseparable from other forms of oppression:

Ableism must be included in our analysis of oppression and in our conversations about violence, responses to violence and ending violence. Ableism cuts across all of our movements because ableism dictates how bodies should function against a mythical norm—an able-bodied standard of white supremacy, heterosexism, sexism, economic exploitation, moral/religious beliefs, age and ability.

Ableism set the stage for queer and trans people to be institutionalized as mentally disabled; for communities of color to be understood as less capable, smart and intelligent, therefore “naturally” fit for slave labor; for women’s bodies to be used to produce children, when, where and how men needed them; for people with disabilities to be seen as “disposable” in a capitalist and exploitative culture because we are not seen as “productive;” for immigrants to be thought of as a “disease” that we must “cure” because it is “weakening” our country; for violence, cycles of poverty, lack of resources and war to be used as systematic tools to construct disability in communities and entire countries (Mingus, 2011).

Internalized Ableism, Oppression and Identity

For those of us who have the kinds of embodied and enminded differences that may be described as disability, living in a profoundly ableist society impacts how we understand ourselves. We might understand disability through negative stereotypes, which can make us think that the label of “disability” does not describe us.

Whether or not we recognize ourselves as disabled, we might not be comfortable with ourselves and others as people with differences that are often devalued by the dominant, ableist culture. We might feel ashamed of our disabilities, or feel pressure to conceal or minimize our differences. Even if we do embrace disability, we may do this anyway to try to mitigate the impacts of ableist oppression.

Everyone has the right to self-identify how they wish, and internalized ableism is not the only reason why someone might not identify with the term “disability.” For example, as Anishinabe disability scholar Heather Norris (2014) explains, within many Indigenous worldviews, difference and diversity are accepted and embraced as part of the “profound interdependency of all life” (p. 54). In this way, the concept of disability may not be relevant to all Indigenous people. People may also identify with other categories instead of (or in addition to) disability. For instance, they might understand themselves as having a medical condition or a chronic illness. People might also understand themselves through the lens of culture. For example, people who belong to Deaf cultures often do not identify with the label of disability (Bartlett, 2018).

Eugenics

The creators of Into the Light: Living Histories of Oppression and Education in Ontario explain the eugenics movement, which came to prominence in the early 20th century, as follows:

Eugenics tried to socially engineer the improvement of the human race by applying the science of evolution to human populations through biology, heredity, and controlled reproduction. Eugenicists thought that social problems were caused by the existence of deviant and inferior people, instead of understanding that social problems are caused by social, political and economic circumstances. Eugenicists believed they could solve social problems and make the human race better by preventing certain kinds of people from being born and allowing some kinds of people to die.

To achieve this goal in Canada, the government used methods such as sterilization, birth control and institutionalization, primarily targeting Indigenous, disabled, Black and poor people (negative eugenics). Eugenicists also advocated controlled selective breeding of human populations with the aim of improving the population’s genetic composition (positive eugenics) (Into the Light, 2022).

The views of early 20th century eugenics proponents were shaped by existing ideologies of racism, colonialism and ableism. The eugenics movement would be brought into question in the mid-20th century as human rights perspectives gained ground in response to the atrocities of World War II, but the racist, colonial and ableist views that the movement promoted were already deeply entrenched in institutions and policies.

The Afterlife of Eugenics in Canada: Disability Income Support and Medical Assistance In Dying

Eugenics ideologies still shape public attitudes and social policy today. For instance, public disability income support programs across Canada leave recipients in deep poverty, without enough money to pay for even basic needs like housing and food.

In contrast, at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, Canadian federal emergency income support benefits for employed people provided each eligible individual with about twice as much money per month as the amounts that disabled people receive from provincial disability income support programs. The pandemic emergency income support program was also much less restrictive, allowing higher earnings exemptions and no reductions in support amounts if spouses or family members also received the benefit.

Disability rights and justice activists have been advocating for increases to disability support rates, asking why disabled people should have to live on so much less than what is considered a reasonable income level for abled people? Some disabled people have pointed out that the community has easier access to death than the supports needed to live, as Medical Assistance in Dying (MAiD) laws have been expanded to allow more and more people with disabilities or illnesses to end their lives with medical support while income, housing and personal supports have remained extremely limited, leaving people in desperate situations (Favaro, 2022).

Digital Story: A Fearie Tale by Sioux Lily Dickson

In her digital story, A Fearie Tale, Artist Sioux Lily Dickson likens her experience of living on Ontario Disability Support Program benefits to a fairy tale heroine’s struggle to survive.

Critical Disability Perspectives as a Counter to Eugenics

Theorists of disability have revealed that “norms” and “ideals” for how people should be are not natural or inevitable, but shaped by political ideologies, including eugenics. Robert McRuer (2012) explains that challenging the idea that everyone should strive to be as close to the “norm” as possible (often through medical means) can create space for the kinds of differences that are often devalued or rejected.

What is at work in [challenges to the dominance of medicalization] is a counter-eugenic will to not eliminate but rather revalue that which is freakish, deformed, twisted, crippled, or in any way atypical (McRuer, 2012, p. 357).

Artist and performance scholar Dr. Jessica Watkin’s textile work, This was not made for your visual pleasure #PleaseTouchMe is a handmade rug purposefully designed to be “ugly to look at” and interesting to engage through other senses such as touch and smell, reflecting a Blind sensory experience. Watkin used a variety of materials with interesting non-visual properties, including scented yarn that she used for a braille text reading “rage.” In its original installation, the piece was displayed at wheelchair user height, further disrupting typical expectations for the exhibition of textile art.

The piece was originally shown in the 2019 Productive Discomfort exhibit at Myseum in Toronto, curated by Dr. Lauren Cullen.

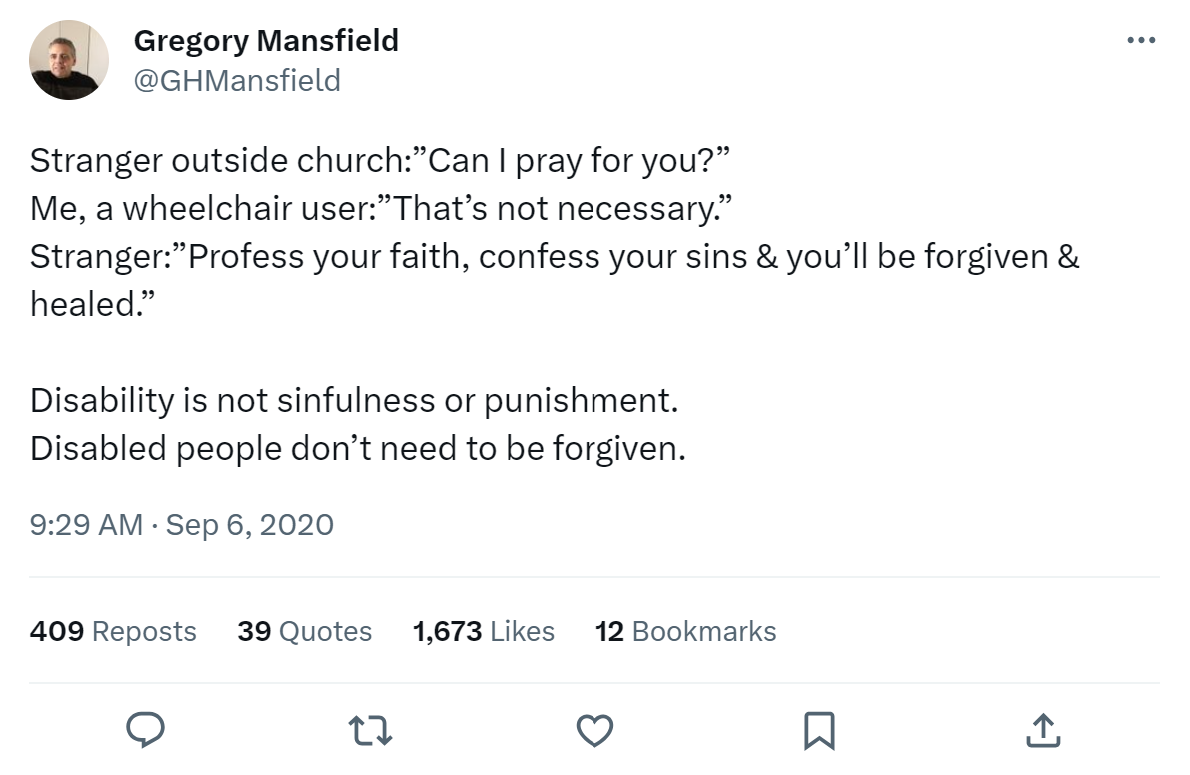

The Moral Model of Disability

In some historical and contemporary contexts, physical and mental differences from the normate have been understood through a spiritual or moral lens. For example, some experiences of mental and perceptual difference have been thought to be caused by spiritual possession (Porter, 2002, pp. 26–31). Physical, mental and neurological differences have also been understood as reflecting spiritual deficiency, or even as a punishment for a moral transgression by the disabled person, their family members or their ancestors. Disability generally has sometimes been characterized as a test of faith or as a tragedy that leads to an opportunity for character strengthening (Retief & Letšosa, 2018, p. 2).

Although it is no longer the dominant way of understanding disability, the moral model of disability has an ongoing impact. In this tweet, lawyer and disability activist Gregory Mansfield describes how a stranger’s moral model-based concept of disability led them to accost him in public:

Activity

Brainstorm Question

What are some common ways that disability is understood through a moral lens today?

The Charity Model of Disability

The charity model of disability positions disability as a personal tragedy and disabled people as objects of pity while casting abled people as their potential benefactors or saviors.

Disability theorist and activist A.J. Withers (2012) explains that the charity model of disability is an obstacle to the social changes that disabled people need:

The entire charity approach is designed to ensure that no real change ever occurs. It is about people doing good for others, it is not about change, it is not about liberation, it is about the agents of charity—the do-gooders feeling better about themselves and the world they live in.

Until recent decades, charitable campaigns, including advertisements and telethons, were one of the few places where disability was represented in the media. These widely-viewed representations typically depicted disabled people in ways that were infantilizing and disempowering (Longmore, 2016). Instead of recognizing disability as a basic part of life and access as a right, they promoted an understanding of disability as undesirable and needing cure, and access as a matter of pity-motivated “kindness.”

Today there are many more representations of disability and disabled people in the media, including ones that challenge stereotypes. Although current charity representations of disability also tend to be less stereotype-driven than they were in the past, they sometimes perpetuate the idea that disability is undesirable and should be overcome through medical means and careful self-management.

For instance, in Canada, the Bell Let’s Talk campaign often features images and stories of elite athletes and well known entertainers successfully coping with mental health difficulties while excelling in their fields. The systemic factors that impact mental health are not addressed by the campaign (Landry, 2016; Sui & Katzman, 2021). Charity campaign materials like these are sometimes cited as positive representations, but they could also be understood as reflecting the “supercrip” trope.

Supercrip

Disability theorist Sami Schalk (2016) explains that “supercrip” representations of disability are said to depict “overcoming, heroism, inspiration, and the extraordinary.” They may also portray “individual attitude, work and perseverance” as the keys to success for disabled people instead of recognizing the importance of promoting access and removing barriers (p. 73).

Following the work of Amit Kama, Schalk makes a distinction between two types of “supercrip” narratives:

- The “regular supercrip” narrative positions mundane activities (i.e. playing a sport, attending a social event) as notable when undertaken by a disabled person (p. 79), reflecting ableist expectations for the lives of disabled people (p. 74).

- The “glorified supercrip” narrative highlights disabled people with outstanding accomplishments (i.e. competing in the Olympics or Paralympics, winning a major award). With their emphasis on overcoming adversity to reach success, “glorified supercrip” representations often make little mention of the privileges that facilitate these achievements (p. 80).

Schalk also introduces a third type of supercrip narrative:

- The “superpowered supercrip” narrative involves the portrayal of a disabled person as having superpowers that “overcompensate” for their disability. This narrative often appears in fiction, but can also be found in representations of real disabled people who use prosthetics or who are labeled as “savants” (p. 81).

Schalk advocates for a nuanced evaluation of “supercrip” representations, calling upon viewers to ask the following questions:

- In what ways is this representation adhering to the multiple variations of the supercrip narrative and in what ways is it not?

- Is the supercrip narrative the only or best way to understand what’s occurring in this representation?

Activity

Non-Profit Representations

Do non-profit organizations led by non-disabled people differ in how they represent disability and difference compared with organizations led by disabled people?

For example, compare the website of Autism Speaks with the website of the Autistic Women and Non-Binary Network (AWN).

Who are the leaders of each organization?

- Are they people with lived experience/members of the community served by the organization?

- Are they family members of disabled people?

- Are they medical experts or other people with a professional relationship to disabled people?

What are the goals of each organization?

- Research for a “cure”?

- Providing supports for people?

- Promoting acceptance?

What terminology do they use?

- People-first and identity-first language?

- Pathologizing or accepting?

How do they depict people?

- What do they show people doing?

- How old are they people they depict? Do they mainly show children or people of all ages? If they mainly show children, what does this imply about their understanding of autism and the focus of their work?

- Does their imagery include people with different identities?

How might these different representations of autism affect how people understand it? How might these representations impact autistic people?

The Medical Model of Disability

The medical model of disability remains the dominant, “common sense” way of understanding disability. It says that disability is caused by problems with people’s bodies and minds. According to the medical model, because genetic conditions, illnesses and injuries are the causes of disability, the way to address disability is through treatments and cures. The medical model supports interventions intended to “fix” disabled people through cure, making them as close as possible to the normate to allow them fit into existing environmental and social contexts (Erevelles, 2011).

By casting differences as problems to be solved, the medical model positions disabled people as lesser in comparison to the (mythical) “norm.” The idea that humans should all meet a normative standard or ideal is based in the eugenics belief that human variation is undesirable and should be eliminated.

Within the medical model, medical experts like physicians and scientific researchers are upheld as the bearers of knowledge, and information about biological processes is understood as the most important information about disability.

Digital Story: No Room for Doubt by Crystal

In No Room for Doubt, Crystal describes how medical experts’ unfounded assumptions about her health and body caused her a serious injury. Her refrain of “I know myself” reveals the power and resistant potential of embodied, experiential knowledge.

Because the medical model retains a dominant position in Western society, resources are often directed toward efforts at developing medical treatments and cures. Medical research can of course be beneficial, resulting in the creation of treatments that can protect or improve health and well-being, or extend life.

- OC Open Captions

- Uncaptioned

Select a format:

Cure and the Medical Model

Disability theorist, writer, and poet Eli Clare explains the complex relationship that disabled and non-normatively embodied/enminded people often have with the medical model and its focus on cure:

I, along with many of us, am alive because of medical technology and the ideology of cure that drives the discovery and development of those drugs, machines, protocols. Yet, cure also responds to the “trouble” of being fat with gastric bypass surgery, dieting, and shaming. I have found body-mind comfort and connection through the medical-industrial complex.

Yet, cure also responds to the “trouble” of significant facial birthmarks with laser surgery and the “trouble” of walking in ways deemed broken by breaking bones, resetting them, stretching them. Without hesitation, I use antibiotics, ibuprofen, synthetic testosterone, appreciating everything they do for me. Yet, cure also responds to the “trouble” of voices and visions with body-mind-numbing psychotropic medication. This maze repeats itself endlessly (Clare, 2017, p. 183).

Although cure can have benefits, when it is the primary focus, supports for disabled people may be overlooked or underfunded, and the importance of access may also be downplayed. Additionally, some people with disabilities and differences do not wish to be “cured.”

A detail from a larger illustration by Josephine Guan, showing a hand holding up a magnifying glass to examine a person with curly hair. This version of the image is presented in shades of blue.