Table of Contents

What is Fat?

Fat is complex to define! There are many definitions, ideas about, and understandings of fat circulating in our culture. How we think and talk about fat depends heavily on context. For example, in physiological terms, fat is conceived of in terms of adipose tissue and materials on and/or in the body. According to Euro-Western ideas of health, fat is talked about as a disease (Land, 2018). Through applying a critical lens to these different definitions of fat, we can understand fat as “a cultural artefact: a bodily substance or body shape that in the particular context of late modern western societies in the early decades of the twenty-first century is given meaning by complex and shifting systems of discourses, practices, emotions, material objects and interpersonal relationships” (Lupton, 2018, pp. 2-3). In other words, thinking critically about fatness requires an understanding of definitions of fatness as based in and shaped by culture.

In fat studies, which is the approach to fatness that we use in this module, fat is both an adjective and a political identity. Fat is used as an adjective to describe a bodily characteristic or experience. In this sense, fat is “a form of non-normative embodiment relating to the presence of adipose tissue” (Cooper, 2016, p. 1). By this, we mean that fatness is experienced on a bodily level. Fat is not a number on a scale, but rather exists in context and experience, such as a larger-bodied person being called “fat” as an insult or not fitting into an airplane seat. Relatedly, fat is a political identity in that fat people are reclaiming the word fat—taking it back from those who have used “fat” as a negative or demeaning word and reinvesting it with positive, neutral, or less oppressive meanings (Wann, 2009, p. xxi). We therefore understand fat as descriptive, reclaimed, and politicized.

Reflection Questions

- What has the word “fat” meant to you previously in your life?

- How is the word “fat” used most often in your experience? Reflect on contexts like media (film, television, music), social media, and health care!

- Have you encountered the word “fat” in a positive and/or neutral context? If so, what was this context and what do you think was the intention behind the positive and/or neutral use of the term “fat”?

What is Anti-Fatness?

A key part of the fat studies definition of fat is an understanding that discrimination on the basis of fatness is real, significant, harmful, and deserving of attention. Referred to also as fatphobia, fatmisia, sizeism, weight-based discrimination, and/or fat-shaming, we use fat activist Aubrey Gordon’s (2021) understanding of anti-fatness as “the attitudes, behaviours, and social systems that specifically exclude, underserve, and oppress fat bodies.” Gordon’s (2021) use of anti-fatness encompasses the harm generated by both individuals and institutions, situating anti-fatness firmly in the realm of culture rather than individualized issues of self-esteem.

In their article, “Mapping the Circulation of Fat Hatred,” Bodies in Translation researchers Jen Rinaldi, Carla Rice, Emma Lind, and Crystal Kotow (2020) explore how anti-fatness manifests in queer women’s and trans folks’ experiences. They find that fat hatred often takes the form of presumptuous advice (e.g., Why don’t you go for a walk? Why don’t you try eating healthier?), disapproving gestures (e.g., people shaking their heads or staring), open humiliation (e.g., harassment), and violent words and acts (e.g., verbal and physical assault). The people that Rinaldi et al. (2020) spoke to experienced intensified anti-fatness in healthcare, public transportation, and recreation and wellness spaces. As a direct result of these manifestations of anti-fatness, participants felt internalized anxiety and shame, out of place, and a sense of un-belonging. Consequently, participants tended to avoid public engagement and confrontation, increasing their risk of isolation or discomfort. Therefore, Rinaldi et al. (2020) argue that anti-fatness ultimately functions to exclude, expunge, and end fat lives.

Anti-fatness is experienced through and in relation to other body markers like race, gender, ability, and class (Rinaldi et al., 2020). Fat activist Da’Shaun Harrison (2021) defines anti-fatness as anti-blackness, writing that “fatness is formed as a coherent ideology through the creation of (anti-)Blackness and therefore does not intersect with Blackness but exists with Blackness itself” (p. 18). Harrison’s (2021) definition inherently connects anti-fatness with racism, colonization, and white supremacy. This definition references the work of fat studies scholar Sabrina Strings (2019), who explores how, by the end of the eighteenth century, pseudo-scientific theories of race had linked fatness to Blackness in the European imagination and, by extension, had also linked thinness to whiteness. Black communities were characterized as naturally disposed to being fat, and this was used by Euro-Western “scientists” as evidence of their inferiority to white people, who were characterized as naturally slender and “civilized.” The fat gendered body, in particular, is racialized, as Black women’s bodies are scrutinized, objectified, and subject to violence for the ways that their fatness connotes inferiority, while white women’s bodies are (self-) regulated and policed to uphold white supremacy (Strings, 2019).

Ultimately, ideals of “slenderness” are used to uphold racial distinctions and white supremacy. Today, anti-fatness as anti-Blackness materializes in several ways, some of which include desirability (e.g., the casting of fat Black bodies as “ugly”), health (e.g., the positioning of Black bodies as inherently diseased and biologically and/or culturally prone to fatness and its associated impairments), and policing (e.g., treatment of Black bodies by the police as simultaneously dangerous, and thus requiring the use of excessive force, and weak, and thus responsible for any harm sustained at the hands of the police) (Harrison, 2021).

Reflection Questions

- Where have you encountered examples of anti-fatness?

- Why is it important to include institutions in definitions of anti-fatness?

- How do you understand the relationship of anti-fatness to other oppressions?

What is Fat Activism?

Once you start examining your everyday life through a fat studies lens, you’ll likely find instances of anti-fatness everywhere! Thankfully, there are groups of people across the world who are working hard to identify where and how anti-fatness operates, create fat-affirming sub-cultures, and re-build societies so that they are inclusive, anticipating, and welcoming of fat people. The people who do this work are called fat activists and their ultimate goal is fat liberation or “the deliberate work of tearing down the systems that have created a world where fat people are denied full participation in society and life” (Ashline, 2021).

One of the most prolific fat activists in Euro-Western culture, Charlotte Cooper (2016), defines fat activism as “the stuff that people generally recognize as activism, but it’s also the relationships between the people doing activism, it is the cultural work they produce, [and] it can be very small moments that happen within or beyond community” (p. 53). She breaks fat activism down into five broad categories:

Political Process

Using existing structures, institutions, tools, and processes of state power (e.g., rights, policy, legislation, letter-writing)

Community-Building

Creating relationships between members of activist communities/marginalized communities (e.g., support or consciousness-raising groups, social spaces/gatherings, fostering alliances/friendships, sharing resources/information)

Cultural Work

Making fat bodies and activist communities visible through art, objects, events, texts, spaces, and places (e.g., public performance art/events, fa(t)shion, sculpture, painting, creative writing)

Micro

Engaging in everyday, smaller, quieter activities (e.g., eating an “unhealthy” food, making a living space accessible, refuting a co-worker’s anti-fat comment, living one’s life as an example of another way of being fat)

Ambiguous

Creating non-conformist fat spaces that emphasize the potential to find joy, fun, and humour in failing to embody the “good fatty” [see below] (e.g., scale smashings, “glorifying obesity” hashtags, Cooper’s group “The Chubsters”)

These five categories are not easily distinguishable or neatly separated in real life, but they do offer a way of understanding fat activism as broad-reaching and highlight the labour that fat people must perform daily just to get by in the world.

The ultimate goal of fat activism, according to Cooper (2016), is to create conditions under which fat lives are more livable (i.e., less marginalized).

Fat Activism Spotlight

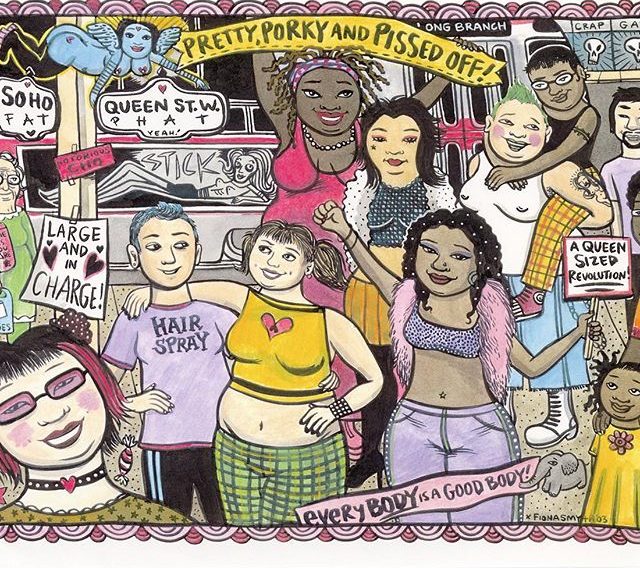

Pretty Porky and Pissed Off

Pretty Porky and Pissed Off was a fat activist and performance art collective, based in Toronto, Canada, who were active from the late 1990s to the early 2000s. Pretty Porky and Pissed Off incited a “queen sized revolt,” as their manifesto below declares. The collective consisted of a core membership of Allyson Mitchell, Tracy Tidgwell, Zoe Whittall, Lisa Ayuso, Joanne Huffa, Abi Slone and Mariko Tamaki with contributions from many including Gillian Bell and Ruby Rowan. From producing and performing shows centered on fat dance and drag across Southwestern Ontario; to direct actions and teach-ins designed to highlight issues of anti-fatness; to producing zines, writing and other cultural productions attempting to resist fatphobia; to hosting fat girl clothing swaps; to lecturing and leading workshops on size acceptance, Pretty Porky and Pissed Off’s fat activism was varied and widespread.

Learn more about Pretty Porky and Pissed off through the Bodies in Translation project Archiving the Ephemeral History of Pretty Porky and Pissed Off, or check out the article “Feeling Pretty Porky and Pissed Off” by Allison Taylor and Allyson Mitchell!

Reflection Questions

- What examples of fat activism have you previously encountered?

- What are some ways that you can incorporate fat activism into your everyday life?

Authors

Allison Taylor, Meredith Bessey, and Calla Evans

Contributors

- Elisabeth Harrison

- Lilith Lee

A line drawing by Allison Tunis of community member and writer, Phillip Barragán, his partner, and friends at an accessibility conference. Phillip is using a power chair, two friends are using mobility scooters, and two are standing. The image shows disabled and able-bodied people living their lives and engaging in everyday fun.