Learning Objectives

- Summarize the implications of the medicalization of body size.

- Offer an overview of the construction of the “obesity epidemic” and a critique of normative weight science.

- Describe current rhetorics around fatness and COVID-19, their implications, and activist and artist responses.

- Provide an overview of anti-fatness in health care and its impacts.

- Examine weight-inclusive frameworks that have emerged to counter medical rhetoric, and their positive and negative impacts (e.g., healthism).

Guiding Questions

- How has fatness been medicalized in the health care system?

- How does medicalization contribute to stigma and subsequent poor health outcomes?

- What alternative health frameworks have been proposed, and what are their strengths and limitations?

- What are some activist and artist responses to anti-fatness within health care?

Health can be defined in many ways, depending on the context. However, one frequently used definition comes from the World Health Organization (2022), which defines health as “a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity.” Health is also often conceptualized as a resource or asset that supports us in living our everyday lives. Many factors influence health, including social status, income, education, social environments, physical environments, genetics, and to a relatively small extent, personal health practices (Government of Canada, 2008).

These ways of thinking about health, however, often ignore how “health” has been constructed as something that is unobtainable for certain groups, such as Black fat people. As Da’Shaun Harrison (2021) writes in their book Belly of the Beast: The Politics of Anti-Fatness as Anti-Blackness:

[F]or one to be healthy, they must not only be non-disabled but must also be in an environment that allows for them to feel mentally secure, psychically safe, and socially well. As such, this means that Black people—especially those of us who exist with multiple marginalized identities—are always already unhealthy because we are always already unsafe (p. 33).

The notion of “health” has been used to bolster the medical industrial complex, and to prop up hierarchies of “healthy” and “unhealthy,” “fat” and “thin,” etc. Metrics typically used to measure “health,” such as the Body Mass Index (BMI), were designed to other, and to separate those who could never be deemed “healthy” from the norm. BMI enables certain people to be labelled as “overweight” or “obese” and to therefore be deemed inherently “unhealthy.” These classifications are rather arbitrary—for example, the cut-off for being deemed “overweight” was lowered from 27.8 to 25 in 1998, in order to match guidelines drafted by the International Obesity Task Force (Butler, 2014). However, these guidelines were funded in part by pharmaceutical companies who manufacture weight loss drugs, calling their validity into question (Butler, 2014).

Although BMI is still commonly used in many health care settings, it has been long known that it is a deeply flawed metric, and is not reflective of someone’s health status (Burgard, 2009; Tomiyama et al., 2016; Your Fat Friend, 2019). In fact, even the inventor of the BMI, Adolphe Quetelet, did not intend for it to be a metric of individual health.

While Quetelet’s work was used to justify scientific racism for decades to come, he was clear about one aspect of the BMI: it was never intended as a measure of individual body fat, build, or health (Karasu, 2016). For its inventor, the BMI was a way of measuring populations, not individuals—and it was designed for the purposes of statistics, not individual health (Your Fat Friend, 2019, para. 7).

For further information on why BMI is an unhelpful health assessment tool, check out this blog post from Health at Every Size dietitian Rachael Hartley, The Many Problems with BMI (Hartley, n.d.).

There is a growing body of critical literature that shows that, despite the common rhetoric, one can be “healthy” at a variety of body sizes, including those deemed “obese”. Weight-inclusive health care paradigms, such as Health at Every Size, have been constructed around this critical science, to counter dominant discourses that position fat as always and inherently unhealthy.

Although this refutation of the claim that fat is unhealthy has import, it is also important to understand the notion of “healthism”—this is a form of medicalization that places health on a pedestal, as the primary focus for the achievement of well-being (Zola, 1977; Crawford, 1980), and labels those who deemed “healthy” as moral, good citizens. Weight-inclusive health frameworks such as Health at Every Size sometimes reinscribe these healthist norms, where only fat people who are “healthy” are seen as worthy, which leaves many, many people behind (Gibson, 2022). Cooper (2016) refers to fat activism that promotes healthist ideals through the metaphor of gentrification, where those who are already marginalized are further sidelined and erased.

Thus, while this module includes some content refuting dominant “obesity” science, the goal is not to necessarily argue that fat people can or should be healthy, but that fat people (and all people) are deserving of respect and appropriate care regardless of their health status. Weight-inclusive, fat-affirming approaches to health care, therefore, remain vitally important: fatphobia in the health care sphere is literally killing people, and it cannot be brushed aside.

We want to reimagine and envision new worlds where health care affirms people in their here-and-now bodies. The work of Bodies in Translation, in part, speaks back and responds to harmful rhetorics around fatness and resists normative ideas about fat bodies. The purpose of this section, in particular, is to also draw attention to activist and artistic responses to anti-fatness in health care; we will draw on fat activist art throughout this section.

Reflection Questions

- How have you been taught to understand health?

- How has your individual access (or lack thereof) to “health” and to supportive health care shaped your understanding of and relationship to “health”?

- Read Gemma Gibson’s article Health(ism) at Every Size: The duties of the “good fatty” (2022) and consider the following question: Can weight-inclusive frameworks like Health at Every Size promote inclusive care for people in all sizes of bodies without contributing to healthism? What would need to change about the frameworks or their implementation to achieve this?

Authors

Meredith Bessey

Contributors

- Allison Taylor

- Elisabeth Harrison

- Lilith Lee

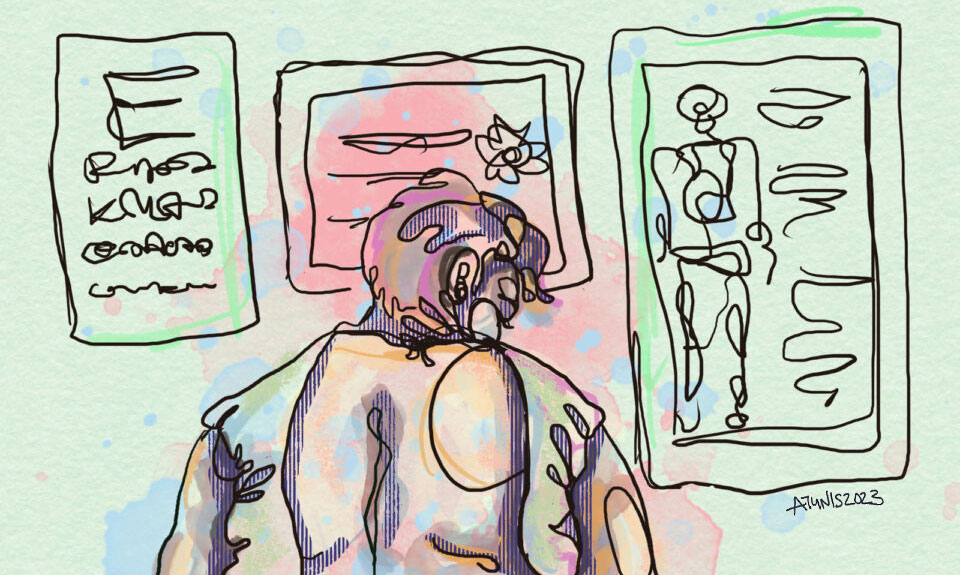

The Weight of Words by Allison Tunis. A line drawing of a fat person with short hair and a goatee, wearing a tank top and shorts. The person stands on a medical scale next to a speech bubble with the words “resistant, high risk, medicalization, BMI, stigma.” Language around fatness and weight in healthcare settings often reveals anti-fat bias. Judgment and pathologization have negative impacts on health, leading to poorer health outcomes overall.