Anti-fatness in health care is rampant, and has deleterious impacts on the health and well-being of fat people. Research shows that anti-fatness (or alternatively, weight stigma, fatmisia, or fatphobia) is common among health care providers and students alike, with professionals and students holding damaging beliefs that fat people are lazy, weak-willed, sloppy, dishonest, unhealthy, non-compliant, and lacking in self-control, among other damaging and inaccurate beliefs (e.g., Bessey & Lordly, 2020; Bessey et al., 2021; Pausé, 2014; Rinaldi et al., 2020).

Rachel Wiley is a queer, biracial poet and performer from Ohio; her poem The Fat Joke (Wiley, 2018) serves as a powerful introduction to the lived experience of anti-fatness in health care settings.

Fat girl walks into the world

and still somehow manages to love her fat body.

And the world says, “Stop glorifying obesity.”

Fat girl walks into the world and says,

“I do not owe you shrinking.”

Anti-fatness is often inaccurately conceptualized as an individual issue, as health care providers who incidentally have unconscious biases that impact the way they treat fat patients, and who simply need to work to overcome these biases. However, as Mikey Mercedes (2022) outlines in her article “No Health, No Care: The Big Fat Loophole in the Hippocratic Oath,” medical fatphobia is violent, violating, innate, and inherent to the health care system. Physicians and other health care providers are educated in a fatphobic educational system that reinforces outdated and harmful beliefs about fat people and their bodies. These biases infiltrate all aspects of health care, and have wide-reaching impacts on the care received by fat people. Fatphobia also intersects with racism, misogyny, ableism, and other forms of oppression within systems (Friedman, 2020), including in health care:

[Anti-fatness] intersects with other social status markers used to restrict access to categories of parenthood and citizenship such as race, ethnicity, income, and ability, often surfacing in reproductive care settings in the form of blame. This blame is leveraged in a way that is used to prop up control of bodies deemed “risky,” as these people are assumed to be “unable” to make “correct” health choices (LaMarre et al., 2020).

These fatphobic beliefs and attitudes have material impacts on the health of fat people. Many cardiometabolic health outcomes that are often blamed on fatness can be connected to experiences of oppression and stigmatization based on weight (Hunger et al., 2015; Vadiveloo & Mattei, 2017). For example, Vadiveloo and Mattei (2017) found that self-reported weight discrimination was related to twice the risk of high allostatic load at a 10-year follow-up, increasing risk of metabolic dysregulation. Fat people are also often ignored and dismissed, or told to simply lose weight when they present with health concerns, leading to inadequate screening and treatment, as well as health care avoidance (e.g. Amy et al., 2006; Drury & Louis, 2002; Lee & Pausé, 2016).

One well-known example of this mistreatment is the experience of Ellen Maud Bennett, who was repeatedly dismissed by her doctors over a number of years, before being diagnosed with terminal cancer and passing away days later. She used her obituary as an opportunity to advocate for awareness of the harms of anti-fatness in the medical space, which received significant media attention.

A final message Ellen wanted to share was about the fat shaming she endured from the medical profession. Over the past few years of feeling unwell she sought out medical intervention and no one offered any support or suggestions beyond weight loss. Ellen’s dying wish was that women of size make her death matter by advocating strongly for their health and not accepting that fat is the only relevant health issue (Victoria Times Colonist, 2018).

Ellen’s story is a poignant reminder that anti-fatness in health care is not about hurt feelings, it is literally life or death for many.

Beyond the ideological beliefs about fatness that drive anti-fatness in health care, anti-fatness also materially shapes the health care space. For example, Fady Shanouda’s (2021) chapter in the book Weight Bias in Health Education addresses the built-in fat phobia in health care that is embodied by medical equipment like Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) machines. In the chapter, Shanouda describes his own encounters with anti-fatness in the health care system:

I am scared to get sick. I am not frightened of the consequences of illness—pain, suffering, discomfort, even death. These are inescapable truths. No, I am afraid of being denied the most basic care because I am fat.

This fear started when, in an offhand comment, my general practitioner conveyed how difficult it might be for me to get a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan given my size. The same doctor has tried to weigh me by balancing each leg on a different scale and has waved off testing my blood pressure because the cuffs in her office were too small. Medical equipment embodies the anti-fat bias inherent in the medical community (p. 30).

These built-in biases contribute to fat people’s fear of getting sick and having to access health care: how will they receive a proper diagnosis and treatment when the equipment is not designed for their body? Other material aspects of the health care context are not designed for fat peoples’ bodies either, such as waiting room chairs, blood pressure cuffs, or even hospital gowns in a bariatric surgery clinic, as Roxane Gay (2018) notes so eloquently in her article What Fullness Is, about her personal experience of undergoing weight reduction surgery,

I told the friend accompanying me that the gown the hospital provided probably wouldn’t fit me, and she said that couldn’t possibly happen, given the nature of my impending procedure. I was right: The gown was indeed too small, and, at six in the morning, I was too tired and too defeated to even laugh or feel any kind of satisfaction for understanding just how shortsighted this world is when it comes to different kinds of bodies.

Video: No Room for Doubt by Crystal

Several stories from the Re•Vision project Through Thick and Thin highlight experiences of medical fatphobia. For example, in Crystal’s story, No Room for Doubt, Crystal describes her experience of being brushed off by a doctor at a walk-in clinic when she has been struggling to breathe, and her subsequent fears about not being taken seriously, which had initially kept her from going to an emergency room.

Reflection Questions

- What feelings or emotions does hearing Crystal’s story bring up for you?

- How does the imagery Crystal uses, of various forms of transportation, reflect the themes in her story?

- How can dismissal, as Crystal discusses at the end of her story, serve as an act of fat activism in and of itself, as well as something that reinforces anti-fatness in health care?

Reproducing Stigma

The Reproducing Stigma project also speaks to experiences of medical fatphobia, specifically for women and trans people who have been labelled “obese” and who are accessing reproductive health care while trying to become pregnant. This project highlights the importance of not only evidence-based health care, but also storied care, where fat people’s stories and experiences are seen as central to achieving equity within reproductive health care (Friedman et al., 2020).

Video: Seeing My Body Differently by Emma Lind

In Emma Lind’s story, Seeing My Body Differently, Emma highlights how medical fatphobia often starts at a very young age, telling the story of how her doctor told her mother, when Emma was only eight years old, to stop putting apple juice in her lunch in order to stop making her fat. This encounter led to a decade of shame, pain, and hunger.

- OC Open Captions

- Uncaptioned

Select a format:

Video: Fear, Fat, Food and Failure. Feminist Ruminations on Birthing by Kelly

In Fear, Fat, Food and Failure, Kelly discusses her early experiences with digestive problems, her subsequent food and eating issues, and her anxiety about whether her body is “good enough,” including to bear children. She describes her turbulent childhood, and the anti-fatness she experienced in her family, and the fear she carries that her fatness might lead to hers or her babies’ death. Kelly’s story highlights her conflicting feelings about her fat body, and the intertwining of mental health, poverty, trauma, and other aspects of her experience.

- Uncaptioned

Select a format:

Video: Too Much by May Friedman

In her story, Too Much, May Friedman describes how she has viewed her body outside of pregnancy with suspicion, as “too fat, too loud, too hairy, too ethnic, far too out of control to ever fit in.” May reflects on her changing relationship with her body before, during, and after her pregnancies, and how, in her own words, her “body actually did [something] right” when it came to pregnancy the first three times, only to eventually encounter unluckiness in that realm too. Was she being punished for being greedy, for daring to take up space?

- OC Open Captions

- Uncaptioned

Select a format:

Reflection Questions

- What are some common themes you noticed in Emma, Kelly, and May’s stories? Conversely, how did their experiences differ?

- How did their experiences of anti-fatness impact Emma, Kelly, and May? What emotions or feelings did their experiences elicit?

- How do Emma, Kelly, and May’s stories work to challenge stereotypical understandings of fatness?

Further Learning: Ragen Chastain’s Weight and Healthcare Newsletter

Ragen Chastain is a fat activist, much of whose work over the past decade has been focused on weight science and health care—she has a great newsletter called Weight and Healthcare that covers many of the topics we have introduced in this module but in greater depth.

Reflection Questions

- If you are a health care student or professional, what have you learned about fatness in your training? Have you learned anything that counteracts dominant ideas about “obesity” as a disease?

- Have you experienced or witnessed anti-fatness in health care settings? What feelings came up for you?

- Reflect on the importance of stories and lived experience in disrupting anti-fatness or fatphobia in health care.

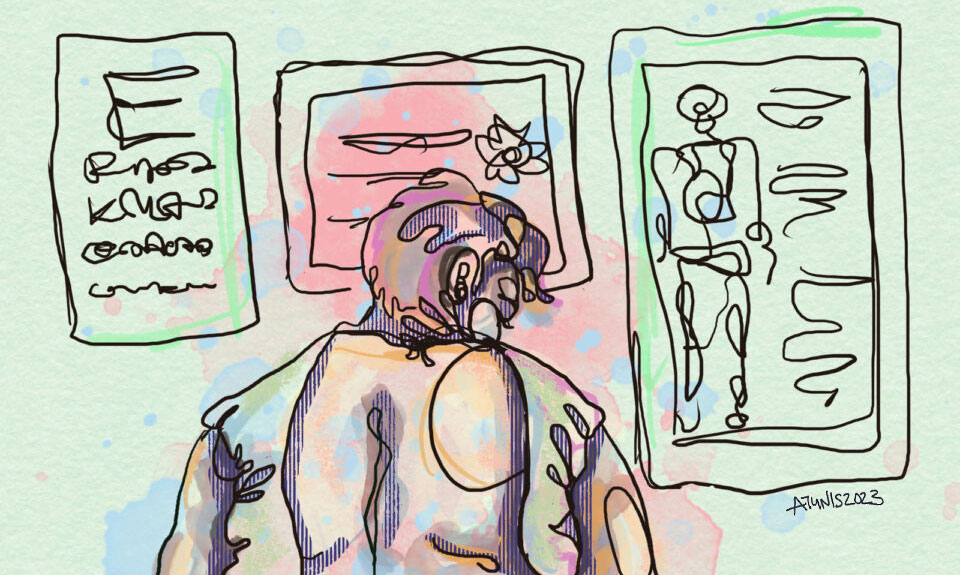

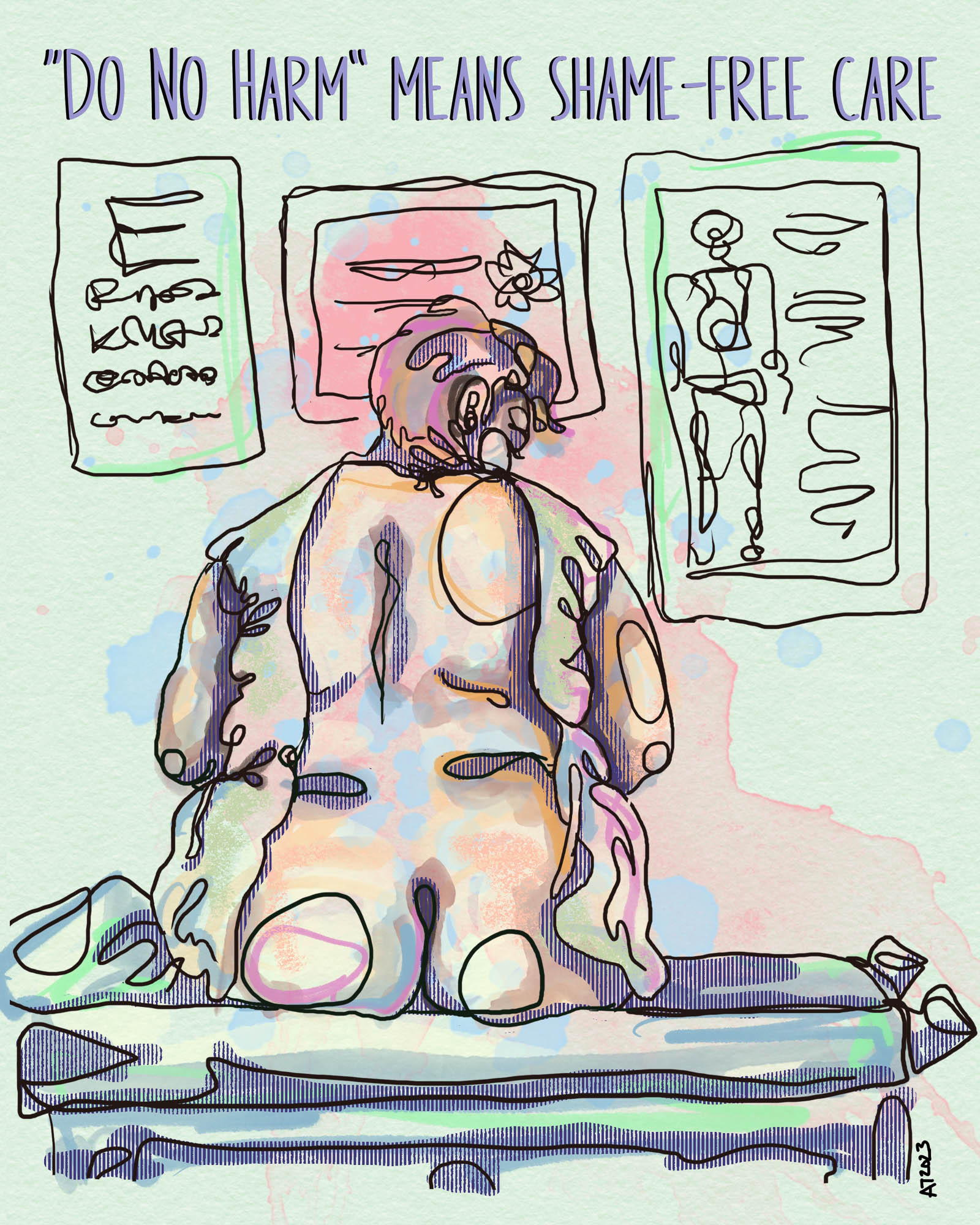

“Do No Harm Means Shame-Free Care” by Allison Tunis. A line drawing accented by green, pink, orange and blue watercolours, showing a fat person sitting with their back exposed by a too-small hospital gown in front of medical posters. This image comes from Allison’s experiences seeking shame-free and weight-neutral healthcare (mostly unsuccessfully), and it raises the question of how fat people seeking health care can feel safe and be vulnerable when doctors and other practitioners continue to judge, make assumptions, deny care, and ultimately cause real harm?